The story of how a young Devonshire man cheated the gallows not just once, nor twice, but three times, is one that has been retold many times and in many formsnote1.

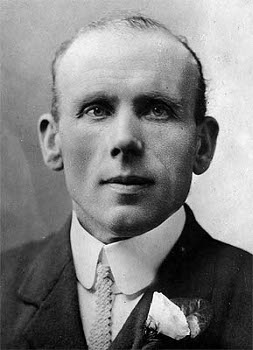

John Henry George Lee was born in August 1864 in the village of Abbotskerswell. On leaving school he was employed as a servant by Emma Keyse, a spinster who lived at The Glen in Babbacombe (or Babbicombe as it was known then), a peaceful seaside hamlet near Torquay. A few years later he enlisted in the navy at Devonport but was discharged through injury after three years. He then went into service under one Colonel Brownlow who lived at Ridge Hill in Torquay; in 1883 he was convicted of stealing silverware worth £20 from his master for which he was sentenced to six months hard labour at Exeter Prison after entering a guilty plea.

Following his release from prison in 1884, Miss Keyse, who had taken a shine to Lee when he first worked in her household, decided to give him a second chance, and he was once again employed at The Glen where his half-sister Elizabeth Harris worked as a cook.

Disaster struck on the 15th November of that year when there was a fire at the house and Emma was found dead with her throat cut. It appeared that the fire had been started by the murderer to incinerate her body, so as to destroy any evidence at the scene. John Lee, then 20 years old, was thought to be the only male in the house at the time and was arrested on suspicion of murder. It was known that he held a grudge against Emma after she had recently reduced his wages, but the evidence against him was purely circumstantial. He was found to have a cut on his arm which he said happened when he broke the window of the dining room to let out the smoke. He was unable to give a satisfactory account of his movements at the time of the murder and following an inquest was sent for trial at Exeter Assizes.

An inquest was held before a jury at St Marychurch Town Hall, starting two days after the murder. Twenty-five witness statements were read including those of the cook Elizabeth Harris and the two other maidservants resident at The Glen, the elderly sisters Eliza and Jane Neck. The jury returned a verdict accusing Lee of being responsible for Emma's death and the coroner directed that Wilful murder by John Lee should appear on her death certificate. Today this presumption of guilt before trial would be regarded as a travesty of justice, but it was normal practice at the time: even if Lee were to be acquitted at his trial, the cause of death written on the certificate would stand.

The trial was held in Exeter Guildhall beginning on February 2nd 1885. Lee was to be represented in court by Reginald Gwynne Templer, a young solicitor who was acquainted with Miss Keyse, making it perverse that he should act for the defence. However, it was claimed that he was known to the Lee family also, and it was Lee's parents who had recommended him. Two days before the trial was due to start Reginald was taken ill and was replaced by his younger brother Charles and the Liberal MP for St Ives, John St Aubyn. Reginald never fully recovered and died on 18 December 1886 from paralysis of the insane - a Victorian medical euphemism usually associated with tertiary syphilis. Adding to the intrigue surrounding Gwynne Templer, there was speculation that he was the lover of Lee's half-sister Elizabeth Harris the cook, who was pregnant by an unknown father at the time of the murder. While he has never been named publicly as the perpetrator, there is a widely held view that he was the murderer, and Lee was only guilty of the subordinate role of covering up the crimenote2.

Lee protested his innocence throughout the trial, but his case was poorly presented with no defence witnesses being called and inadequate cross-examination of the prosecution witnesses. The prosecution case was unconvincing too, amounting to little more than that Lee, a young man with a criminal record, was the only male in the house at the time of the murder and was found with blood on his clothes after the event. It was also suggested that Lee's coat and trousers smelled of paraffin oil, but evidence from the medical practitioner cast doubt on whether this was true of the trousers when he first examined them, suggesting that this exhibit had been tampered with:

Although the evidence against Lee was little more than circumstantial, the jury took a mere 40 minutes to find him guilty and he was sentenced to death by hanging. On being asked by the judge as to why he had taken the sentence with such equanimity, Lee replied:

Prior to 1868 executions in Exeter (and elsewhere in the UK) were public spectacles that drew vast crowds of morbidly curious onlookers. For example, the last public execution of a woman in Exeter was that of Mary Anne Ashford who was found guilty of the murder of her husband. Her hanging outside the County Gaol on 28 March 1866 was watched by as many as 20,000 spectatorsnote3. Following passage of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act in 1868, executions had to take place inside prisons; apart from the officials responsible for carrying out the judicial killing and the prison chaplain, only accredited members of the press were allowed to witness the event.

The execution method used in Great Britain at the time of Lee's execution was known as the long drop. In this procedure, instead of letting the victim fall a standard distance, the person's height and weight were used to determine an appropriate length of rope to use to ensure that the neck was broken without decapitation occurring during the drop.

Lee's execution was set to take place in Exeter Prison on 23 February 1885. He wrote a long letter to his half-sister Elizabeth Harris 12 days before this date in which he questioned the truthfulness of her testimony and that of the other servants at The Glen at his trial.

The night before the fateful day Lee claimed to have had a vision in which an angel told him he need have no fear as he wouldn't be executed because he was innocent.

The scaffold to be used was originally housed in an old prison hospital building. It was removed from this site pending its demolition, and was re-erected in the van-house in 1882. This was to be the first execution to be carried out in the new location. As was the usual practice the drop was pre-tested by the executioner, Yorkshireman James Berry in this instance. This is the procedure that was followed according to the prison governor Edwin Cowtannote4:

No further testing took place on the Sunday and the executioner Berry remained in the prison until the Monday when the execution was to begin at 8am.

The Chief Constable of Devon, Gerald de Courcy Hamilton, describes the remarkable events that unfolded during the attempted execution of Lee:

Hamilton went on to say that Lee was subjected to a third unsuccessful hanging attempt, and maybe even a fourth: other eyewitness accounts contradict this, saying that Lee was strung up for the drop no more than three times. After the the flaps failed to open for the third time, following an animated discussion between the officials present the execution was abandoned and Lee was returned to his cell. The prison Medical Officer takes up the story:

The scaffold platform had two sets of hinges. Those at the outer edge allowed the two halves to swing open downwards when the release mechanism was activated; the other hinges ran along the entire length where the two halves met in the middle. These hinges were held in place by draw-bolts at one end which were released by pulling a lever, allowing the hanging prisoner to drop as both halves swung down.

On the morning following the day of execution two clerks of works made a careful examination of the apparatus. Rather than jamming because the boards were too close at the centre, as had been thought at the time, in the Report on the Cause of Failure of the Machinery of the Scaffold the two men concluded that the equipment hadn't been reassembled correctly when it was moved to the van-house.

After the Home Secretary Sir William Harcourt had been informed of the circumstances of Lee's execution he immediately passed an order commuting the death sentence to life imprisonment. In answer to a question in the House of Commons on 23rd February 1885 he replied:

There was much disquiet in the press and in parliament over the affair and the way executioners were appointed on an add hoc basis; on 24 February 1885 The Guardian in its editorial called for more efficient executions. The Home Secretary bowed to pressure and ordered that an enquiry be held into the matter.

Lee was released from prison in 1907 after serving 22 years in Portland Prison. He became a minor celebrity, touring the country giving his own version of the story which he published in 1912 in book form as The Man They Could Not Hang. A silent film of his story was also made in this year. He married a Devon woman in January 1909 with whom he fathered two children. He abandoned his wife for another woman, travelling with her to the USA in 1911. He lived until the age of 80, dying on 19 March 1945 in Milwaukee.